Wednesday, June 30, 2004

Someday, after I've left this office job, I'll probably look back on it fondly. I tend to do that with all my past employment adventures:

Assembling barbecues and lawn mowers at giant warehouse stores wasn't bad, except for repeating, "No, ma'am, sorry, I don't actually work for Home Depot, so I have no idea where the doorknobs section is."

Being a gofer for producers and directors was interesting. Especially taking their car to get smog-checked, buying toys for their kids, refilling their anti-freak-out medication at the pharmacy and picking up dozens of cans of Tender Vittles for the director's best friend, Miss Whisker-Schnookiekins. Apparently, that's what the magic of movie-making is all about, baby.

What else? Let's see... Working in the music box warehouse, where I boxed boxes; escorting Cookie Monster through the offices of the L.A. Times; packing food rations for Israeli soldiers (complete with halvah candy bars); placing bets in Vegas for a professional gambler--all fascinating experiences.

I'm not being sarcastic. I wouldn't want to do those jobs again, but I learned a lot about the world and the human condition from those gigs. My parents would say that hard work builds character.

Well, if that's true, you could erect a skyscraper of personality working construction. Since my dad was in the business, he hooked me up each summer I was in college. I went all over NYC, used different power tools, met tons of incredibly bizarre individuals.

On one site, I had to use a jackhammer all day. That was the worst. Tearing up the floor -- and my body -- with this loud, nausea-inducing hydraulic implement of destruction. The cement dust got into every pore. Then the other guys on the site complained about the concrete cloud I was creating, so I watered down the ground before I ripped into it again. That just spewed cement mud all over me. I limped home, every muscle aching, deafened from the noise, looking like some kind of hobbling crusty monster. It would take a couple of hours to wash off the dirt - the gray, brown, black soot came off in layers like I was a human gobstopper. Then I'd start all over the next day.

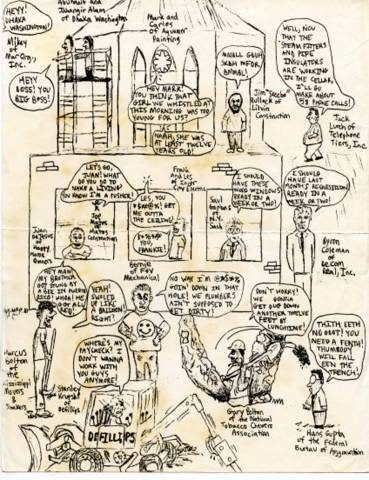

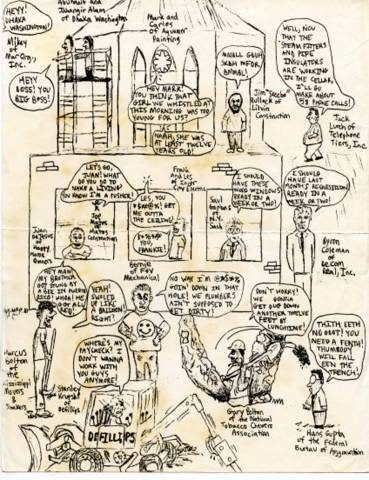

And my most memorable experience was the Bronx job. I spent a whole summer up at the VA Hospital on Kingsbridge Road, a few subway stops up from Yankee Stadium. They had a non-denominational chapel that needed renovating. It was a huge undertaking; there were dozens of subcontractors milling about there every day. They were from all over -- a veritable UN of skilled labor -- and on the surface these people seemed like an assortment of stereotypes. But eventually I got to really know -- and love -- every one of those guys. Before I went back to school the next semester, I drew this cartoon to commemorate it all.

Abuhanif and Jahangir Alam were a few of many masonry men from Dhaka, the capitol of Bangladesh. Friendly guys, they would shout "Hey, Big Boss!" every morning. Not that I had any authority on the job; they just didn't say much else in English. Eventually they got my name right; it took me a while to do the same, 'cause every one of them had "Mohammed" as a first name.

For whatever reason, it's the construction workers' code to hoot and holler at every woman that passes by. Mark and Carlos didn't follow the rules exactly - they waited only 'til jailbait girls were in earshot before they let loose with "Heyyyyy, mama! Ooh, chickie-chickie-babeeeeee!"

Jim "Skeebo" Bullock was a close business associate of my dad's. Ever since he moved up from Raleigh, Skeebo worked very hard at subcontracting jobs. But not so much at his diction. Maybe it was just me having trouble understanding that southern drawl one gets from living in "Nawcarrlahnah".

Perhaps today, with the widespread use of cellphones, Jack Lurch would've been able to utilize a hands-free remote to continue his conversations while insulating the pipes and, uh, fitting the steam.

Joe Matos was a funny little loudmouth, a carpenter with a Napoleon complex. Picture a Puerto-Rican Joe Pesci saying, "Hey, I know your old man, he's awright. There's a lotta pricks in this business. Your father - not a prick."

Walk through the job on any given day and you'd hear -- though not always see -- Frankie the 'Lectrician and his boss, Les, cursing each other out from within the ceilings, the walls, etc. It was as if the chapel was haunted by a couple of foul-mouthed poltergeists.

There's more money to be made in the private sector, but you could easily get screwed. With city jobs, you'll get paid, sooner or later. But the paperwork and red tape and change orders and delays -- by vendors and general contractors Saul Garbas and Byron Coleman -- could drive you nuts waiting.

Loved the conversations between laborers Juan DeJesus and Marcus Bolton. Juan would tell long stories about his messed-up Brooklyn apartment or life back in Puerto Rico, and Mississippi Marcus would just kinda repeat what he said in his own words.

Juan: Man, my brother was drinkin' so much, he had to go in the bushes.

Marcus: Yeah, was takin' a piss, right, Johnny?

Juan: Yeah! And this bee came along and he got stung. Y'know, down there!

Marcus: Yeah, nailed him right on the pecker, right, Johnny?

Juan: Man, he said it hurt, but didn't mind it getting all red and shit...

Marcus: Yeah, swoled up like a muthafucka, right, Johnny?

Bernie the plumber kinda scared me. He was a big guy who was pissed off all the time, and heavily peppered his rants with angry four-letter words. But I probably didn't need to worry so much - I heard he thought this fuckin' cartoon was fuckin' funny.

The bane of the job was accessing a sewage pipe that was 12-feet underground. It was a fragile clay pipe, which meant we couldn't excavate the whole thing with a bulldozer, but digging by hand, we soon hit heavy boulders, and had to hire a hoe-ram to break through. The fixtures on the damn machine never worked right, and Stanley Krupski would threaten to walk off the job. Gee, Operator Krupski, Krups you!

Then poor Hans Gupta would arrive. I can't remember if he was the safety inspector or the VA's construction engineer, but he was always rattling on in his thick Indian accent about someone possibly falling in the trench, when he was the only one facing that peril, walking around the hole in his suit and low-traction Oxford shoes.

Gary Bolton, Marcus's brother, was unwaveringly optimistic about finishing the job. He'd spit his tobacco juice and keep digging, even as it rained every other day that summer. He'd clear out a few feet one day, and the rain would wash the dirt back in that night. Me, Marcus and Juan and others also jumped into the hole to help, but no one was as positive-thinking as Gary.

Juan: Man, we're like a buncha amateurs on this job.

Marcus: Yeah, couple o'rookies, right, Johnny?

Juan: Shit man, we ain't never gonna get done.

Marcus. Yeah. We gonna be down here for the rest of our lives, right, Johnny?

But Marcus was wrong; Gary was right - it eventually got done, and we all moved onto other jobs. I'd see those guys on other construction sites, and when I went back in New York I'd occasionally hear stories about other stuff they were up to.

Well, I better get back to shuffling papers. Hard to believe I'm gonna miss this office crap someday. But who knew I'd look back on the Bronx job as such good times...?

Assembling barbecues and lawn mowers at giant warehouse stores wasn't bad, except for repeating, "No, ma'am, sorry, I don't actually work for Home Depot, so I have no idea where the doorknobs section is."

Being a gofer for producers and directors was interesting. Especially taking their car to get smog-checked, buying toys for their kids, refilling their anti-freak-out medication at the pharmacy and picking up dozens of cans of Tender Vittles for the director's best friend, Miss Whisker-Schnookiekins. Apparently, that's what the magic of movie-making is all about, baby.

What else? Let's see... Working in the music box warehouse, where I boxed boxes; escorting Cookie Monster through the offices of the L.A. Times; packing food rations for Israeli soldiers (complete with halvah candy bars); placing bets in Vegas for a professional gambler--all fascinating experiences.

I'm not being sarcastic. I wouldn't want to do those jobs again, but I learned a lot about the world and the human condition from those gigs. My parents would say that hard work builds character.

Well, if that's true, you could erect a skyscraper of personality working construction. Since my dad was in the business, he hooked me up each summer I was in college. I went all over NYC, used different power tools, met tons of incredibly bizarre individuals.

On one site, I had to use a jackhammer all day. That was the worst. Tearing up the floor -- and my body -- with this loud, nausea-inducing hydraulic implement of destruction. The cement dust got into every pore. Then the other guys on the site complained about the concrete cloud I was creating, so I watered down the ground before I ripped into it again. That just spewed cement mud all over me. I limped home, every muscle aching, deafened from the noise, looking like some kind of hobbling crusty monster. It would take a couple of hours to wash off the dirt - the gray, brown, black soot came off in layers like I was a human gobstopper. Then I'd start all over the next day.

And my most memorable experience was the Bronx job. I spent a whole summer up at the VA Hospital on Kingsbridge Road, a few subway stops up from Yankee Stadium. They had a non-denominational chapel that needed renovating. It was a huge undertaking; there were dozens of subcontractors milling about there every day. They were from all over -- a veritable UN of skilled labor -- and on the surface these people seemed like an assortment of stereotypes. But eventually I got to really know -- and love -- every one of those guys. Before I went back to school the next semester, I drew this cartoon to commemorate it all.

Abuhanif and Jahangir Alam were a few of many masonry men from Dhaka, the capitol of Bangladesh. Friendly guys, they would shout "Hey, Big Boss!" every morning. Not that I had any authority on the job; they just didn't say much else in English. Eventually they got my name right; it took me a while to do the same, 'cause every one of them had "Mohammed" as a first name.

For whatever reason, it's the construction workers' code to hoot and holler at every woman that passes by. Mark and Carlos didn't follow the rules exactly - they waited only 'til jailbait girls were in earshot before they let loose with "Heyyyyy, mama! Ooh, chickie-chickie-babeeeeee!"

Jim "Skeebo" Bullock was a close business associate of my dad's. Ever since he moved up from Raleigh, Skeebo worked very hard at subcontracting jobs. But not so much at his diction. Maybe it was just me having trouble understanding that southern drawl one gets from living in "Nawcarrlahnah".

Perhaps today, with the widespread use of cellphones, Jack Lurch would've been able to utilize a hands-free remote to continue his conversations while insulating the pipes and, uh, fitting the steam.

Joe Matos was a funny little loudmouth, a carpenter with a Napoleon complex. Picture a Puerto-Rican Joe Pesci saying, "Hey, I know your old man, he's awright. There's a lotta pricks in this business. Your father - not a prick."

Walk through the job on any given day and you'd hear -- though not always see -- Frankie the 'Lectrician and his boss, Les, cursing each other out from within the ceilings, the walls, etc. It was as if the chapel was haunted by a couple of foul-mouthed poltergeists.

There's more money to be made in the private sector, but you could easily get screwed. With city jobs, you'll get paid, sooner or later. But the paperwork and red tape and change orders and delays -- by vendors and general contractors Saul Garbas and Byron Coleman -- could drive you nuts waiting.

Loved the conversations between laborers Juan DeJesus and Marcus Bolton. Juan would tell long stories about his messed-up Brooklyn apartment or life back in Puerto Rico, and Mississippi Marcus would just kinda repeat what he said in his own words.

Juan: Man, my brother was drinkin' so much, he had to go in the bushes.

Marcus: Yeah, was takin' a piss, right, Johnny?

Juan: Yeah! And this bee came along and he got stung. Y'know, down there!

Marcus: Yeah, nailed him right on the pecker, right, Johnny?

Juan: Man, he said it hurt, but didn't mind it getting all red and shit...

Marcus: Yeah, swoled up like a muthafucka, right, Johnny?

Bernie the plumber kinda scared me. He was a big guy who was pissed off all the time, and heavily peppered his rants with angry four-letter words. But I probably didn't need to worry so much - I heard he thought this fuckin' cartoon was fuckin' funny.

The bane of the job was accessing a sewage pipe that was 12-feet underground. It was a fragile clay pipe, which meant we couldn't excavate the whole thing with a bulldozer, but digging by hand, we soon hit heavy boulders, and had to hire a hoe-ram to break through. The fixtures on the damn machine never worked right, and Stanley Krupski would threaten to walk off the job. Gee, Operator Krupski, Krups you!

Then poor Hans Gupta would arrive. I can't remember if he was the safety inspector or the VA's construction engineer, but he was always rattling on in his thick Indian accent about someone possibly falling in the trench, when he was the only one facing that peril, walking around the hole in his suit and low-traction Oxford shoes.

Gary Bolton, Marcus's brother, was unwaveringly optimistic about finishing the job. He'd spit his tobacco juice and keep digging, even as it rained every other day that summer. He'd clear out a few feet one day, and the rain would wash the dirt back in that night. Me, Marcus and Juan and others also jumped into the hole to help, but no one was as positive-thinking as Gary.

Juan: Man, we're like a buncha amateurs on this job.

Marcus: Yeah, couple o'rookies, right, Johnny?

Juan: Shit man, we ain't never gonna get done.

Marcus. Yeah. We gonna be down here for the rest of our lives, right, Johnny?

But Marcus was wrong; Gary was right - it eventually got done, and we all moved onto other jobs. I'd see those guys on other construction sites, and when I went back in New York I'd occasionally hear stories about other stuff they were up to.

Well, I better get back to shuffling papers. Hard to believe I'm gonna miss this office crap someday. But who knew I'd look back on the Bronx job as such good times...?

Post a Comment